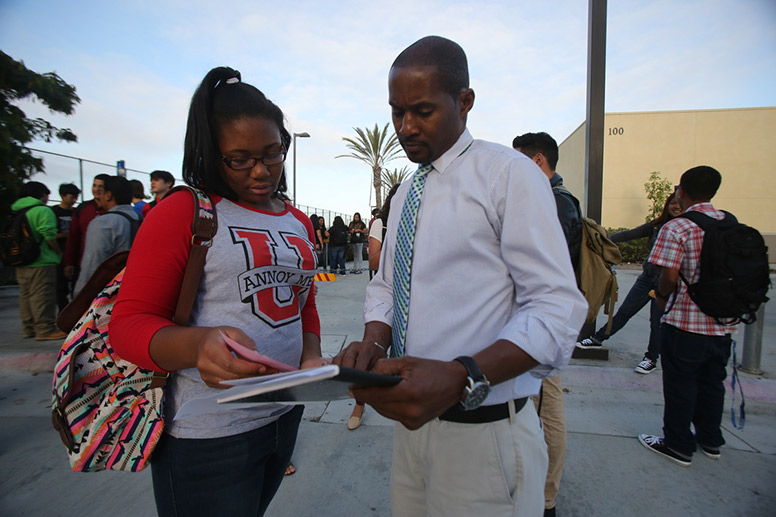

Lincoln High School Principal John Ross talks with a student. | Photo By Jamie Scott Lytle

Lincoln High School Principal John Ross talks with a student. | Photo By Jamie Scott Lytle

San Diego Unified has a huge problem on its hands.

Data just released by the district shows troubling news about the class of 2016, the first class being held to new stricter graduation requirements. Among the revelations in the data:

• Only 59 percent of the class of 2016 is currently on track to graduate. That means about 3,000 students are currently falling short.

• The numbers are even more discouraging for troubled high schools like Lincoln, where less than 30 percent of students are on track.

• Most startling is the outlook for English learners. A mere 9 percent of them, districtwide, are currently in line to graduate. Nine percent.

• Only 24 percent of students with special needs are on track to graduate.

The data has been a long time coming. Last summer, when I wrote that thousands of students in 2016 could fall short of revamped graduation requirements, the district said that it had the situation under control. The problem was, it still didn’t have the data that showed how many students were on track graduate in 2016.

Now, however, that data is ready – and it casts a harsh spotlight on where students currently stand.

Here’s how the district got here: Five years ago, San Diego Unified realized that a large number of students were making it through high school without the classes that would get them into the University of California or California State University systems.

The problem was worse for schools like Lincoln, Hoover and Crawford, which tend to have higher concentrations of black and Latino students, as well as a lot of English-learning students.

That drew calls from the ACLU and other advocates who said the district wasn’t giving students of color fair access to college prep classes.

The school board stepped up. Kind of. In 2009, it promised to look at the issue, and formed a committee to make recommendations as to how San Diego Unified classes could be better aligned with UC and CSU entrance requirements.

Around that time, Education Trust-West, an education policy advocate and research organization, conducted a transcript audit of San Diego Unified graduates that found:

• Wide disparities existed between schools that were meeting students’ needs and those that weren’t.

• Black and Latino students had less access to college prep classes.

• Black and Latino students weren’t doing as well as their peers in college prep classes.

Armed with the findings, the school board in 2011 upped the ante. All students had to take and pass a series of college preparatory classes, known as A-G courses, by the year 2016 or they wouldn’t graduate.

At the time, it looked like a success. The school board charted a course for the district, schools would fall in line and adjust their schedules accordingly, and more students would have access to college prep classes than ever before. That was the thinking, anyway.

But the numbers show that schools haven’t met the demands. Most ironically, black, Latino and students learning English – the very students the initiative aimed to help – are farthest behind.

Here’s how students are doing in specific San Diego high schools:

The district took umbrage earlier this year with the implication that it hasn’t done sufficient work to meet students’ need. The district has invested a lot of time and energy in ensuring all students have access to college prep classes and is committed to equity, a district spokesperson told me.

A presentation the district will deliver at this week’s school board meeting highlights some of that work. Last year, colorful posters explaining graduation requirements were distributed to every school, for example. Letters have been sent home to students’ families. Counselors have helped students create four-year plans.

Regardless, the recent numbers underscore just how much work the district has to do in the short amount of time between now and 2016.

Much of this work will fall on Cheryl Hibbeln, who was a standout principal at Kearny High before Superintendent Cindy Marten put her in charge of the High School Resources Office.

That means she’ll be making sure district principals are offering the classes students will need to graduate.

And some serious changes need to happen. For example, students need to pass three years of college preparatory math. But the district has long offered Unifying Algebra, a kind of watered-down math course that doesn’t count toward the new graduation requirements or admission to UC/CSU schools. Twelve high schools still offered the course as late as last year.

Many of the A-G requirements – four years of English, three years of math, history/social science and science – aren’t so different from what high schools have offered for years. The biggest sticking point, aside from an extra year of math, is the new requirement to take two years of the same foreign language.

Moving forward, the district will try to help students recover credits by offering more courses in summer school. And it may try to change some of the graduation requirements. English learners, for example, may not have to take two years of a foreign language if they’re already considered bilingual.

Students with special needs may be able to take sign language in place of a world language.

Some changes make sense – why should bilingual, Spanish-speaking students be required to take two years of another foreign language – but they also open the door to gently dulling the original policy.