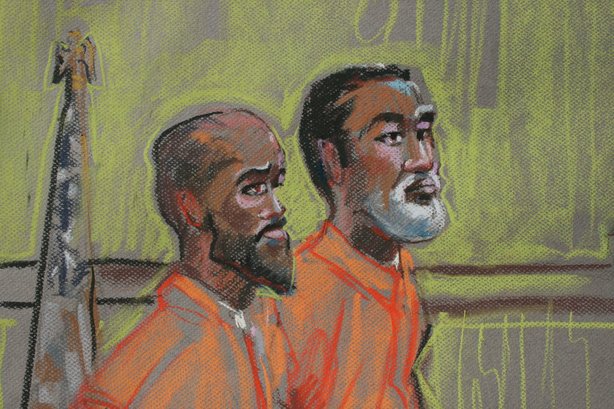

Mohamed Mohamud and Issa Doreh are shown in this 2010 courtroom drawing by Krentz Johnson.

National Security Agency Director Keith Alexander said this week he does not know how to ferret out terrorist plots on U.S. soil without collecting the phone records of every American. Other supporters of the controversial NSA surveillance say there are examples of how it has led law enforcement to real terrorists. And one example comes out of San Diego.

Earlier this year, four Somali immigrants were convicted of sending money to the terrorist group al-Shabaab. And the subject of the case came up in June before Congress, when national security officials spoke at an unusual public meeting of the House Intelligence Committee.

Their goal was to clarify and justify NSA surveillance following leaks by former contractor Edward Snowden. FBI Deputy Director Sean Joyce offered an example of how the NSA’s massive database of call logs was used to nab terrorists and the people who finance them.

“The NSA provided us a telephone number only in San Diego that had indirect contact with an extremist outside the United States,” Joyce said.

The FBI, he said, took it from there.

“We were able to under further investigation and electronic surveillance that we applied specifically for this U.S. person with the (U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance) court, we were able to identify co-conspirators and we were able to disrupt this terrorist activity,” Joyce said. “He was providing financial support to an overseas terrorist group that was a designated terrorist group to the United States.”

Soon after Joyce’s remarks, defense lawyer Joshua Dratel sat fuming in his New York office. He knew Joyce was referring to his client San Diego taxi driver Basaaly Moalin and three other Somalis. A jury convicted them in February of sending $8,500 to al-Shabaab in Somalia. What he didn’t know, until the congressional hearing, was how the case against the men got started.

“It’s outrageous that the government saw fit to release this information only for political gain, not to help someone defend himself and exercise their right to a free trial,” Dratel said. “That wasn’t good enough.”

Dratel said Joyce’s comments revealed new details he believes could have changed the outcome of Moalin’s trial.

The FBI investigated Moalin in 2003 but found no links to terrorism. Dratel said he would have explored that fully at trial. Also, Joyce characterized Moalin’s contact with an al-Shabaab member as indirect.

But that’s not what federal prosecutors said in court. And they have proof: Much of the government’s case against Moalin and the others was based on FBI wiretaps of their phones.

Still, Dratel insists he would have argued the case differently had he known all the facts.

“In a pretrial context, we would have been able to get to the bottom of this. Post-trial the standard is always higher and harder,” Dratel said. “There’s a judicial interest in the courts of finality, of not looking back.”

Dratel asked for a new trial. But last month a San Diego federal judge said no. Dratel has appealed the decision.

“The area definitely needs legal clarity,” said Rick Pildes, a constitutional law professor at New York University.

Pildes said the government now follows the policy of disclosure, when evidence is a product of NSA surveillance. But that was not the Justice Department’s policy a few years ago, as witnessed in the San Diego case against the four Somalis.

Meanwhile, civil liberty groups like the Electronic Frontier Foundation are watching. The foundation’s lawyer, Hanni Fakhoury, said a crucial defense argument is the NSA’s dragnet of domestic phone calls tramples on constitutional privacy rights.

“The argument has always been that the Fourth Amendment generally requires police to obtain a search warrant before they conduct a search,” Fakhoury said. “By obtaining these records without a search warrant, they violated the Fourth Amendment.”

Assistant U.S. Attorney William Cole, who helped prosecute the case against the four San Diego men, declined comment. But in court papers, he contended the records used in the case belonged to the phone company. And since the call logs and not the content of those calls were turned over, there was no Fourth Amendment violation.

Pildes said while the government views the convictions of the four Somali men as an NSA surveillance success, the issue is more complex. Any sensible debate must weigh the costs against the benefits.

“To take the view that there are no benefits and it’s all costs, or it’s all benefit and no potential costs, is more of an ideological position, I think, than the realities would suggest.”