Marti Emerald has proclaimed today Lawrence McKinney Day. McKinney is one of three black officers to take a top post at the San Diego Police Department. He retires Thursday. | Video Credit: Nicholas McVicker

By Megan Burks

Retiring Assistant Police Chief Reflects On Race, Gangs and the Budget, Aired July 30, 2013 on KPBS

[audio:http://speakcityheights.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/MCKINNEY_rad.mp3]

The trial of George Zimmerman, President Barack Obama’s candid comments on race and last week, a national summit that drew attention to Chicago’s alarming rate of black-on-black crime. As the nation talks about race with renewed energy this summer, mid-city residents are reflecting on the headway Lawrence McKinney has made on race relations in their community.

The retiring assistant police chief is the third black officer to rise to the seventh floor at police headquarters. He’s been with the San Diego Police Department for 30 years, serving first as an undercover narcotics officer in area high schools and later on the motorcycle, gang, vice and robbery units. He became captain of the mid-city division in 2008 and assistant chief in 2011.

McKinney sat down with Speak City Heights to talk about his work in mid-city, how he views the police’s role stamping out gang violence and his chief concerns for the department: the budget and officer retention.

Historically, we’ve had to be vigilant of a tension between young, black males and law enforcement. Did that factor into your decision to join the police force?

As a young man growing up in Tacoma, Wash., I was frequently stopped by the police, so I know what it’s like to be challenged for no good reason out there other than I’m a young, black male. As a young, black man, I’ve had guns put in my face when I hadn’t done anything but just because I was a young, black man in the wrong place at the wrong time.

So, I wanted a long time ago to make differences as a black man within the organization, affecting change from the inside. That was always a goal, but not from an activist-type standpoint. What I wanted to do was get in and demonstrate that I was no different than any other good cop, but I’m a black man. What I had hoped to do was increase the level of respect that other people had for black people in general, because they would see me and think, “You know what, this is a good cop.”

I think that I have been relatively successful in that, but I recognize there’s still a lot that needs to be done by both the people who remain in law enforcement and the people who are thinking about getting into law enforcement in the future. I don’t know if this is a struggle that will ever end. It is something that will certainly get better. It’s something we have to remain vigilant on and just keep driving that message that capable men and women are not dictated by race, or anything else for that matter – they are just capable men and women – and hopefully we’ll get to the point one day in this nation when everybody recognizes that.

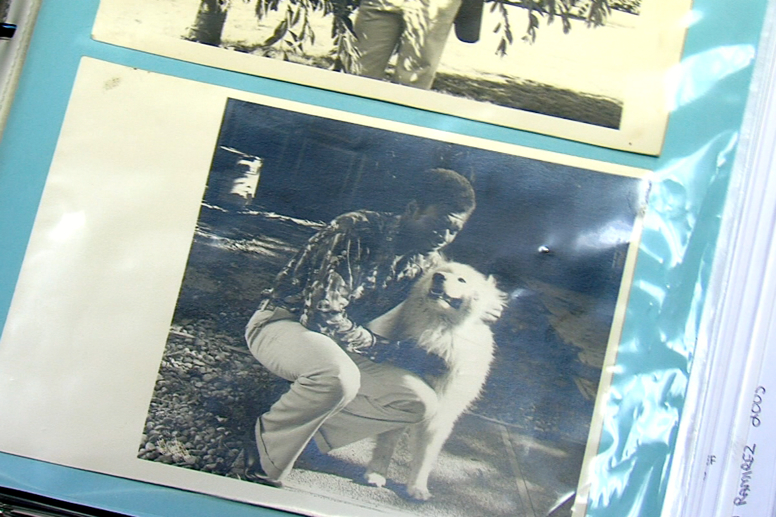

McKinney as a young man in Tacoma, Wash. | Photo Credit: Nicholas McVicker

Young recruits often end up in diverse neighborhoods like City Heights for their first assignments. What advice would you give them?

Keeping an open mind to cultural differences and different perspectives. We tend to think sometimes that everyone thinks the same way that we do and that’s just not the case – particularly in areas of high diversity, some of our areas that have lower socio-economic status, where people tend to be less educated.

One good example from my own career: Officers came to me frustrated because we were working a gang investigation out in southeastern San Diego. The officers were frustrated because they couldn’t get a high level of cooperation from the witnesses in the area. The officers felt that we’re the heroes of this story. “We’re coming in, we’re trying to solve the crime, so why are these people resistant to that?”

They weren’t seeing things from the perspective of a lot of people of color – that sometimes law enforcement is not viewed as the hero of the story. Sometimes, it’s quite the opposite. But giving them an understanding of that helped to bridge the gap.

There were similar frustrations among officers when you got to the mid-city division. What changes did you make to help?

The officers were frustrated. The community was frustrated. So I wanted to implement some things that I hoped would alleviate some of that pressure and it began by trying to instill a sense of pride in these officers.

That involved doing stuff like having my car parked out in front. So I didn’t park my car on the other side of the gates, locked up with everything else. I parked out in front of the division. And it wouldn’t be uncommon for officers to see me out there picking up trash. If there was trash in our parking lot, I would pick it up myself, hoping that the officers would see that if the captain can bend over and pick up trash in the parking lot, we can too.

Then I started working on things to connect officers to the community. For instance, officers had developed a habit of taking all their breaks at the station. So they’d go for eating breaks, administrative breaks, they’d do everything in the station. My biggest thing was, who’s out there on the streets if everyone’s in the station? And I wanted to get across to them that there are a lot of people who are very supportive to law enforcement, but you won’t know that unless you get out there and meet them.

So I actually made a moratorium. I stopped everyone from coming back to the station to eat. I forced them to go out into the community. I got a lot of resistance, but eventually they got it.

The great part of it was, at community meetings, people would come up and thank me for infusing all these new officers into the community. They thought we got these new officers. We didn’t get any new officers. They were just seeing the officers that worked there more often.

And then I tried to ensure each rank was accountable to the public, so that involved me getting out there. I remember in the beginning, I went to every community meeting – every one of them. It was grueling, but what I wanted to do was set an example for the lieutenants. If the captain can be out here, you need to do it because it’s your area. And the community responded in kind. So it was the police reaching out and the community reaching back, and I think we achieved something that hadn’t been seen in mid-city for a long time – a good cooperative relationship between the community and the police.

Assistant Chief Lawrence McKinney hugs a City Heights resident at a retirement party the community threw for him. He attended every community meeting when he first became captain of the mid-city division – a task he says was “grueling” but necessary to build trust. | Photo Credit: Megan Burks

Proof of that relationship can be seen in the fact that mid-city residents threw you a retirement party Saturday. But the relationship is still missing for some. How do you reach them?

By talking with these people, going to the meetings, then taking the messages back to the officers so officers don’t hear about a particular concern from the community – because that sets up and us and them – but from their commanding officers.

One of the things that we dealt with in that regard had to do with sitting people on the curb. There were a lot of problems with it in the community for cultural reasons, but the officers’ feeling is, it’s something that they need to do for safety reasons.

So I sat down with my officers and we talked about that. We talked about how it can be perceived when you take someone and you sit them down there on the curb. What does it mean to a black person, me included, above and beyond the uniform, to get sat down on the curb? I wouldn’t appreciate it. I would think it’s like going way back to the ’60s.

But they weren’t hearing it from someone whom they might perceive as some activist out there in the community; they were hearing it from one of them.

But officers still do sit people they’ve detained on the curb.

It happens because there are some situations where an officer feels that it’s the safest thing that he or she can do right then. I always make sure that my officers understand that I wouldn’t second-guess them on that. They’re getting paid for their judgment. They’re getting paid for their common sense. So if they’re in an alley in the middle of the night and they’re responding to a call of gang members involved in shootings and fights, I’m not going to dictate to them from home what they should and shouldn’t be doing out there.

They’ve gotta make those calls, but they should be ready to answer. If I find out that somebody sat someone on the curb, I’m going to ask them about it and you gotta be ready to tell me, “This is why I did it.” And it should make sense.

One of the disagreements you had with your officers was over the station’s involvement with Gospel Fest, an event that combines ministry and low-riders in an effort to reach gang members.

The red flags were going up for me and my officers. It was off the charts. Absolutely not. We can’t risk all these gangsters in here. The danger level is there with rival gangs. If rival gangs get in there, are they going to throw down right in the middle of this gathering?

So I talked with our community partners, worked with the churches and became convinced that we should give it a shot. The biggest thing occurred to me when we agreed to have a meeting at my station and all the cars came in. I heard a commotion outside and I went outside to see what was going on and there were all these people who had congregated around the lowriders.

From my standpoint, we had been trying to get people to meetings the whole time I was there. You get the main players, the same people coming over and over again to meetings, but you don’t get all those other people. Well, I was out there and I was seeing between 50 and 100 people – and people who I couldn’t get anywhere near a police station. So I knew then the idea was there. They were on to something.

And then it was a matter of going back to the officers and talking to them about it, sharing those same observations and letting them know that we are there to serve all the people in the community. We needed to reach everyone – that dope addict out there, that gangster out there. We are their police, too.

Gospel Fest is in its fourth year now and has never had an act of violence. In fact, I think the worst thing that has happened is someone complained that the music is too loud.

Despite these kinds of efforts, the number of San Diego kids joining gangs hasn’t slowed. What do the Police Department and community need to do to tackle the city’s gang problem?

We are doing a lot of that through the gang commission. We have a very active gang unit within the Police Department, but it goes way beyond that.

I don’t believe that locking people up is the answer. There’s a great community and a greater societal issue out there that needs to be addressed. I also don’t believe that the Police Department is the proper venue that that issue needs to be addressed by. We are a part of it, but we shouldn’t be the focal point.

What we need to do is educate people and strengthen families. Like we find in a lot of African-American families, the father figure is virtually non-existent. So, we could make a difference if those figures were introduced into the mix. There are enough studies and enough positive examples that show that works. Now obviously, that has nothing to do with the police. And the police can’t come up with money for jobs programs, which I think are an integral part of this.

But the police can work with people to educate families about the signs of kids going into gangs and things like that so they can take the appropriate steps if that’s going to happen. And then of course, the police have to be ready to step in and do our part, and our part is a lot of the enforcement.

Now, having said that, I don’t believe now you throw people away forever. Because I’ve seen that people can come back. And we have to be open enough, and this is where it again crosses over into the police, we have to be open enough to accept that people can come back. And a lot of these people want to give back to the community. They want to help with gangs, or narcotics or substance abuse, so we should be open to that.

Looking forward, what is the San Diego Police Department’s biggest challenge?

We are struggling to recover from years of budget cuts. A lot of people like to look at San Diego as a small town. I know that’s great for tourism and things like that, but the fact of the matter is San Diego is the eighth largest city in the United States and it has the same types of problems that go with being a big city. Unfortunately, our mentality is it’s a small town so we just need a small police force.

Through those cuts, we started losing the ability to do lots of things. For instance, out there in mid-city, we were reduced to one community relations officer. When those budget cuts hit, you have to start cutting back on the special stuff. So you go back to our core function. And the core function of the police is to be out there in those black-and-white cars answering radio calls. But there’s a lot more to police work – the undercover gang detectives, the undercover narcotics detectives, the guys who are going for the heart of the problem before the guys in the black-and-whites get there. So when you start taking those people out of the equation because you don’t have enough money to staff them, it has an impact.

The biggest problem we are facing is the budget and rebuilding. And that speaks volumes in and of itself that we’re not looking at the future for a new bar, we’re trying to get back to where we were in 2009.

And the budget issue goes into the next biggest problem: retention. I think over the next three or four years, 50 percent of the Police Department is going to become eligible for retirement. That’s a lot of expertise that’s going to be leaving. The new people have a lot of motivation and enthusiasm, but that is no substitution for experience. Our police force is getting younger and younger and younger so we have to look at ways to retain officers.

People will argue, “Why do we need more police if crime is down?” They’re not taking into account that those officers out there are stretched thin. That thin blue line is ready to snap and, when it does, what happens then? If you have a chance to reinforce it, why wouldn’t you do that before it snaps?

McKinney and current and former mid-city officers at a retirement party hosted by Cherokee Point Elementary Principal Godwin Higa. | Photo Credit: Megan Burks

What are you most proud of when you look back on your career?

The San Diego Police Department is a premiere law enforcement agency in the country. San Diego is a different kind of city. A couple of years ago, I was back at the FBI national academy with law enforcement executives from all over the world. I got the sense then that things are radically different here in how we interact with the community, how the community perceives us. One of the things I’m proudest of is having been a positive part of that.

It’s one of the reasons why I spent my three years as a captain at the mid-city division when I could have gone, and in fact, was ask if I wanted to move on to other commands. There are other commands that are easier to work, I’ll tell you that right up front.

But I wanted to stay there because people saw me on the street as a person of color in uniform. They could see the gold. They didn’t know what it means, but they knew that it’s something different than the other officers. They see that and it gives them some hope in the system. They can see me and see that, you know what, maybe there is hope and maybe a person of color can get somewhere and maybe I can get there.

Councilwoman Marti Emerald has proclaimed Tuesday Lawrence McKinney Day in San Diego. The Police Department will honor him with a traditional walkout ceremony Thursday. McKinney and his wife, Angi, will retire in Texas. Their daughter, Denise, works in the department’s dispatch center.