Refugee children participate in an after-school tutoring program at the Somali Bantu Association of America in City Heights. The Somali Bantu ethnic minority group came to the United States more recently than Somalis who traveled here in the 1990s. Because they’re still gaining their footing on U.S. soil, their children are at high risk of dropping out of school. | Photo Credit: Brian Myers, Media Arts Center San Diego

Refugee children participate in an after-school tutoring program at the Somali Bantu Association of America in City Heights. The Somali Bantu ethnic minority group came to the United States more recently than Somalis who traveled here in the 1990s. Because they’re still gaining their footing on U.S. soil, their children are at high risk of dropping out of school. | Photo Credit: Brian Myers, Media Arts Center San Diego

By Megan Burks

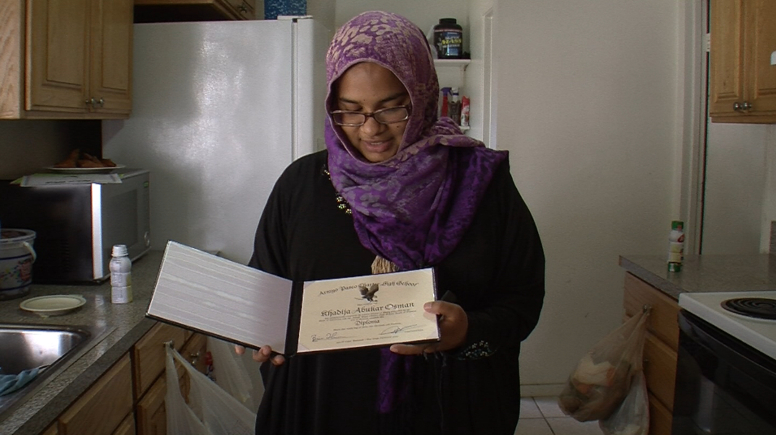

Khadija Osman, 18, shuffles a stack of certificates, one for making the honor roll and several others awarded by teachers. She just graduated from Arroyo Paseo Charter High School in City Heights and is heading to UC Merced in the fall to study biochemistry.

Khadija Osman shows off her diploma from Arroyo Paseo Charter High School July 2, 2014. She’ll be the first in her family to go to college. | Photo Credit: Megan Burks Khadija Osman shows off her diploma from Arroyo Paseo Charter High School July 2, 2014. She’ll be the first in her family to go to college. | Photo Credit: Megan Burks |

In Somalia, where her family comes from, girls were much less likely to go to school than boys. Here in the United States, Somali girls attending San Diego city schools are surpassing their male counterparts academically.

Generally, boys are more likely to drop out of school than girls. The dropout rate for middle and high school boys in the San Diego Unified School district was 1.25 percent during the 2012-2013 school year; it was 0.81 percent for girls.

But leaders in the local Somali community say refugee boys are at much higher risk of dropping out than the general school population, especially if they’re a Somali Bantu ethnic minority, which came to the U.S. more recently. They say boys often are drawn into fights and, like many refugees, lack resources and struggle with language. San Diego Unified does not keep data by ethnic group or immigration status, but said the dropout rate for English learners of all ethnicities was 3.06 percent in 2012-2013.

The graduation gap is feeding a rapid gender shift for the Somali community – one that’s tricky to navigate for young women like Osman.

When Osman learned she was accepted to a university an eight-hour drive away, she got a lot of pushback from her sister. That’s because Osman helps with the household and her nieces and nephews. It’s customary for Somali girls to help look after siblings and other younger relatives.

“There’s girls that would love to go to college but because of all the responsibilities put on us, you know, taking care of the house, and helping parents with translation and appointments, you know, we’re not able,” Osman said. “It’s annoying because a lot of the guys take it for granted.”

Osman believes that’s why some refugee boys drop out – school is just not a priority for them. But Oliva Espin has a different take on why refugee boys have a harder time than girls. She’s a professor emerita at San Diego State who studies psychology and immigrant women.

“Women find jobs immediately, because women clean, cook, take care of old people, they do the same thing they had always done,” Espin said.

Refugee men, on the other hand, often have skills or degrees that don’t quite translate to the U.S. job market. Espin’s own father worked as a lawyer in Cuba but had to get a job sorting mail when he moved his family to the U.S. in the 1960s. She says boys often see their fathers and older brothers stagnate while girls see their mothers and sisters rising to meet the challenges of living in a new country.

“The women have to do things that they would not have done back there in terms of supporting the family. And the girls are seeing that,” Espin said. “The other thing is, most teachers are women. Boys don’t have that many role models.”

Isha Aweyso and her mother, Nuriya Abshiro walk through the Little Mogadishu district of City Heights. | Photo Credit: Brian Myers, Media Arts Center San Diego

Isha Aweyso and her mother, Nuriya Abshiro walk through the Little Mogadishu district of City Heights. | Photo Credit: Brian Myers, Media Arts Center San Diego

Isha Aweyso, 17, will start her senior year at Health Sciences High and Middle College, a charter school in City Heights, in the fall and is on track to go to a university. Wearing an intricate headscarf and vibrant traditional dress, she said boys get distracted at school because they can wear whatever they want.

Click here to hear from young Somali men who defied high drop out rates and are now working to improve conditions in Somalia. Click here to hear from young Somali men who defied high drop out rates and are now working to improve conditions in Somalia. |

“As long as they get their education and make their family proud, (girls are) fine with that,” Aweyso said. “Boys, they worry too much about whether or not their clothes look perfect on them and if that specific group is going to want them.”

Unlike Osman, Aweyso has the full support of her female relatives when it comes to higher education.

Her mother, Nuriya Abshiro, said she’s really happy her daughter can go to school and get a job. It’s something she wanted for herself, but by the time her family earned enough money to enroll her, she had to flee to a refugee camp in Kenya.

But here’s the difference between Aweyso and Osman. Aweyso wants to stay local and go to San Diego State. She’ll be around to help raise her brothers and sisters. And she’ll be a greater support to her family once she has a degree.

Osman said she also knows she’ll have to put her degree to work to support her family. And that’s OK with her, as long as she gets to go to UC Merced, which has the smaller class sizes she believes she’ll need to be successful.

“The thought of telling my dad I want to go away to college was kind of terrifying,” Osman said. “But then I told him why I want to go and he said, ‘You know, at this point, I trust you. You’re old enough and you know what’s best for you.’ So he gave me his blessings.”

Both Osman an Aweyso said they hope to become high school teachers, serving as role models for the refugee girls – and boys – who come after them.

Below: As refugee girls gain more independence, their families are having to come to terms with their less traditional choices. We ask Nuriya Abshiro what she thinks of her daughter Isha Aweyso’s nose piercing.