El Cajon Boulevard divides the Kensington and Teralta neighborhoods in San Diego, Feb. 9, 2016. | Photo Credit: Claire Trageser

El Cajon Boulevard divides the Kensington and Teralta neighborhoods in San Diego, Feb. 9, 2016. | Photo Credit: Claire Trageser

By Claire Trageser and Megan Burks

![]()

San Diego’s El Cajon Boulevard and its four lanes of traffic doesn’t look like much of a border, but it divides two starkly different neighborhoods.

|

Head north of it and you’ll quickly leave the liquor stores and ethnic markets behind and move into a neighborhood of single-family homes that become progressively pricier with each passing block. Head south and you’ll be surrounded by apartment buildings, many housing immigrants from Mexico and refugees who’ve fled civil wars in East Africa and Southeast Asia.

The two San Diego neighborhoods, Kensington and Teralta, are directly next to each other but worlds apart.

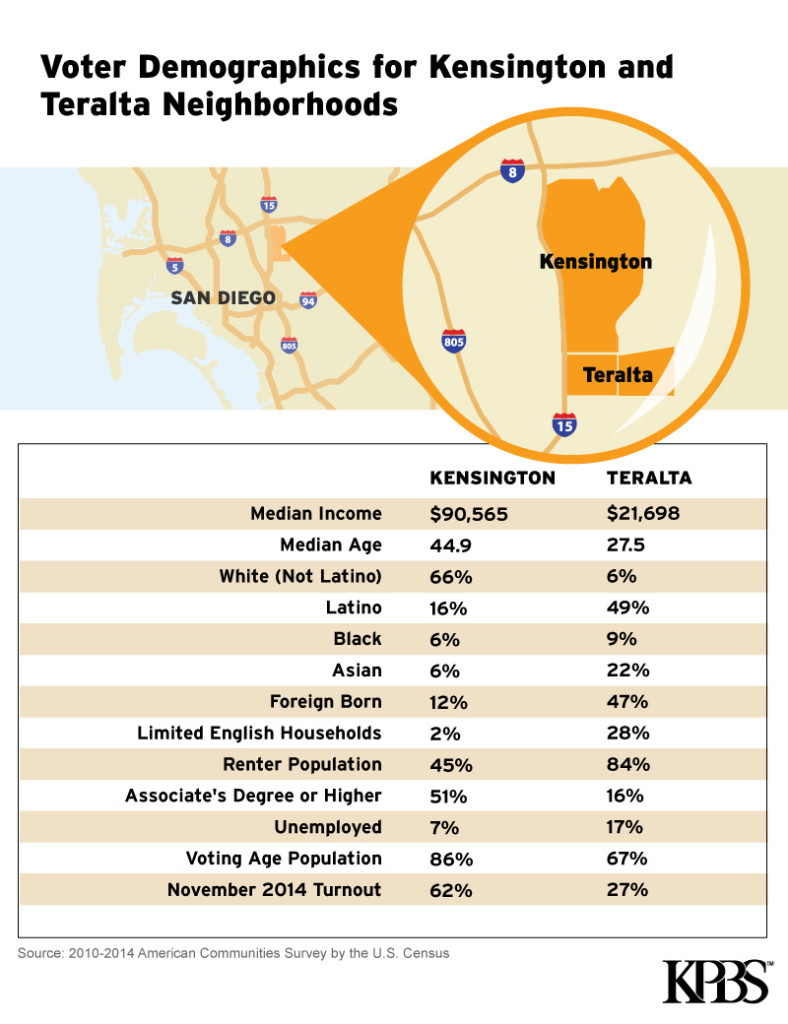

Kensington’s median income is $90,565, while Teralta’s is $21,698, according to U.S. Census data. In Kensington, 66 percent of the residents are white; in Teralta, 6 percent are white. Zoom a little deeper and 47 percent of Teralta’s diverse residents are foreign born compared to 12 percent in Kensington.

These differences feed into a huge gap in voter turnout.

In the 2014 general election, 62 percent of registered voters in Kensington cast ballots. One of its precincts had the third highest turnout in all of San Diego, at 70 percent. The Teralta neighborhood in City Heights had 27 percent voter turnout, and its precincts were among the city’s lowest.

Yet residents in these divergent neighboring communities will be asked to vote on the same issues this year — from raising San Diego’s minimum wage and possibly the state’s to setting aside funds to fix the region’s crumbling roads. And they will decide together — if they vote — who will represent them on the City Council.

The question is whether low-turnout Teralta will continue to allow high-turnout Kensington to make the political decisions for both of them.

Kensington’s bustling commercial area has an organic grocery store and local shops and restaurants, Feb. 5, 2016. | Photo Credit: Nic McVicker

Kensington’s bustling commercial area has an organic grocery store and local shops and restaurants, Feb. 5, 2016. | Photo Credit: Nic McVicker

Kensington ‘embraces’ voting

In Kensington, resident Peter Dennehy likes the community feel of his upper middle-class neighborhood. He’s lived there for almost nine years, and his mother has been there for 15 years.

|

Dennehy, who’s hosted fundraisers for local political candidates and attended debates at a church five blocks from his home, said voting is a tradition for most of his neighbors.

“It’s a neighborhood that embraces participation at every level,” he said.

The 50-year-old is pretty sure he’s never missed an election since he turned 18 and could vote.

“Honestly, I was raised that way,” he said. “I went to vote with my parents, and so that behavior was modeled.”

Kensington has a bustling commercial area with an organic grocery store and lots of local shops and restaurants. Every afternoon and evening, it’s filled with residents walking to do errands or get dinner, strolling with their dogs or taking their kids to the park.

Dennehy said the opportunity to interact with neighbors attracts to Kensington people who want to be involved in their community. It also may help to explain why they get out to vote, he said.

Prominent politicians live there, too. Among them: Democratic Rep. Susan Davis and former Republican Mayor Jerry Sanders. Sanders is often spotted by neighbors on his daily walks.

A man walks past Our Lady of the Sacred Heart in the Teralta West neighborhood of City Heights, Jan. 20, 2016. The Catholic church offers services in English, Spanish and Vietnamese. | Photo Credit: Megan Burks

A man walks past Our Lady of the Sacred Heart in the Teralta West neighborhood of City Heights, Jan. 20, 2016. The Catholic church offers services in English, Spanish and Vietnamese. | Photo Credit: Megan Burks

In Teralta, embracing a new home

As you travel south from Kensington’s cafes and playground, the homes steadily decrease in value and the shops start to sell liquor, not organic produce.

In less than a mile you’ll be in the heart of City Heights’ Teralta neighborhood. Its frenetic center is filled with people from all over the world catching buses to service industry jobs or walking to one of the dozens of Vietnamese and East African supermarkets.

|

One of them is Mohamud Osman, whose family is from Somalia.

He turned 18 last year and said he’ll be voting for the first time in June.

“Voting is a way for us people to have a voice — and not just voting for presidency (or) laws like legalize this, legalize that,” Osman said.

He’s eager to vote for his next City Council member and on quality-of-life issues, including raising the minimum wage. He registered to vote late last year just so he could sign a petition to get the measure on the ballot. A San Diego minimum wage initiative will be on the June ballot, and a statewide measure could be on the November ballot.

While Osman is adamant about having a voice in the election, he represents in part why turnout in his neighborhood dips as low as 14 percent in some elections.

One-third of Teralta residents aren’t old enough to vote, undercutting its civic power.

In 2012, the community was redistricted to give Latinos a stronger voice on the San Diego City Council. The new lines netted a population that was half Latino. But age slashed that voting bloc nearly in half, and the district re-elected Councilwoman Marti Emerald, who is white and a Democrat.

It’s likely Kensington carried much of Emerald’s win. Nearly 90 percent of residents there are above the voting age.

Osman’s family is also representative of many households in his neighborhood, in that his mom and siblings are among the nearly half of Teralta residents born outside the United States. Many can’t vote because they’re living in the country illegally or can’t afford the $680 processing fee to become U.S. citizens.

But Osman said most of the immigrants and refugees in Teralta are like his mom – too busy trying to build a new life to establish that tradition of voting the way Kensington resident Dennehy’s mother did.

Mohamud Osman and his friends talk about presidential candidate Bernie Sanders’s showing in the Iowa caucuses, Feb. 8, 2016. All four say they plan to vote for Sanders. | Photo Credit: Megan Burks

Mohamud Osman and his friends talk about presidential candidate Bernie Sanders’s showing in the Iowa caucuses, Feb. 8, 2016. All four say they plan to vote for Sanders. | Photo Credit: Megan Burks

“We don’t pay attention to a lot of things because we want to know what can we do to have more income,” Osman said. His dad was the sole breadwinner in the family, but he died seven months ago from complications of pneumonia. He worked as a security guard.

Sometimes, Osman said, it’s discouraging to know that Kensington voters are deciding the elections for Teralta voters.

“It makes me definitely want to vote less in a sense,” Osman said. “But I can’t. I want to set an example for people.”

Campaigning across neighborhoods

Tom Shepard is a San Diego political consultant behind many high-profile campaigns for city and county offices. He said Teralta residents shouldn’t be quick to assume candidates for office will skip over their neighborhood to canvass high-turnout Kensington’s manicured streets.

“It is a realistic concern, but I think one mitigating factor in this election cycle is that we’re anticipating a relatively high turnout in the November election as a result of the presidential campaign,” Shepard said.

“And if history is any measure — 2008 and 2012 in particular — there will be a significant turnout of voters in City Heights for the November election,” he said. “So candidates that don’t have a strategy to connect with those voters in June might find themselves far behind the eight ball when it comes to attracting them come November.”

Xema Jacobson, who ran Emerald’s successful City Council campaign in 2008, said the key to winning in such divergent communities as Kensington and Teralta is not to ignore the low-turnout area, just to approach it differently.

“With active voters, you can go in and identify them and follow up with phone calls and that’s it,” Jacobson said. “With people who don’t vote all the time, you spend a bit more time with them. It’s not just a phone call, but on Election Day you go knock on their door, ask, ‘Do you need a ride? Do you need childcare? Do you need something to get you to the polls?’”

Longtime Kensington resident Jodi Cleesattle said she understands those pressures her Teralta neighbors feel.

“The poorer you are, certainly the more pressing issues you may have on your mind, to where voting or learning about particular candidates is less of a priority,” she said.

Cleesattle, 47, said just because a wide spread in demographics exists between her neighborhood and Teralta, that doesn’t necessarily mean there’s a deep political divide between the two neighborhoods.

“We all want better schools, safe neighborhoods, streets without potholes, all those same kinds of concerns,” she said.