Central Elementary School teacher Cindy Robinson, pictured in 2009, works with students in her kindergarten class. | Photo Credit: Sam Hodgson

Cutbacks are now the norm at San Diego Unified School District but unless you’re a parent or teacher at a school, it can be difficult to gauge the true impact of budget reductions.

Soon-to-be Superintendent Cindy Marten, who previously served as principal at Central Elementary in City Heights, spoke about how those cuts affected her former school at an April Voice of San Diego event.

She said the school had “lost and lost and lost millions of dollars,” a statement we later fact checked and found to be barely true.

The point Marten aimed to make in that conversation was significant. She was focused on the dollars principals have to invest in needs at their schools, a pot she referred to as her “instructional core.”

Indeed, budget figures released by the school district show Central saw more than a 60 percent drop in that funding in the last nine years.

That’s not to say the school’s overall budget decreased.

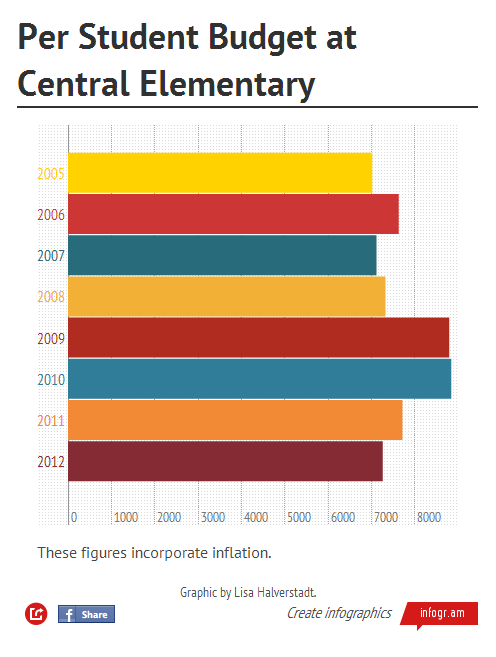

Here’s a look at Central’s planned per-student spending from 2005 to 2012. Those figures are adjusted for inflation and remained somewhat consistent over the last several years.

But discretionary funds principals have to make key hires and grants they can use to invest in educational needs have followed a different trajectory.

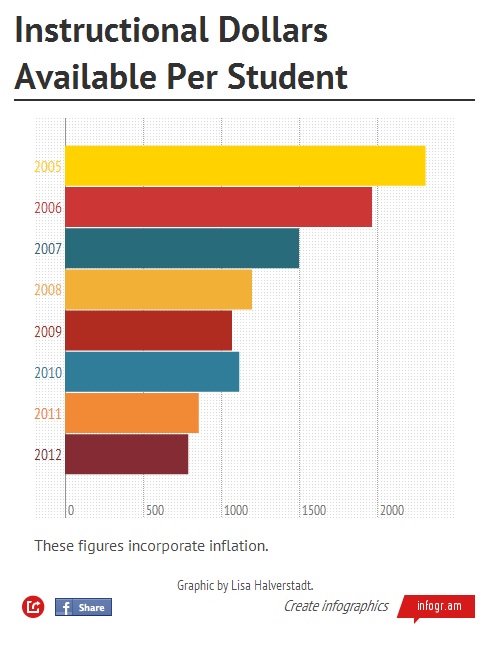

At Central, available funding fell from about $2,312 a student in 2005 to about $790 per student in 2012.

Here’s a look at that steady but quite dramatic decrease.

Marten and current principals at a handful of elementary schools in the district say those cuts forced schools to let go of vice principals, full-time counselors and specialists who coached students in math and reading. There are also fewer available dollars to train teachers.

When Marten arrived at Central as a teacher, the school had four reading recovery teachers, two staffers charged with teacher development, two teachers who specialized in enhancing math instruction and two vice principals.

Those ranks dwindled by the time Marten took the helm as principal in 2008 and she said she found herself wondering how her predecessor could afford so many resources. She quickly realized that drops in instructional funding would make her tenure much different.

Other principals describe similar experiences.

In today’s environment, they say, any available instructional money must be routed to required educational needs. That means staffers who provide supplemental support, including nurses and counselors, are less present in the district’s elementary schools.

“Most principals talk about bare bones,” said Juan Romo, principal at Golden Hill Elementary. “It is pretty much bare bones.”

Principals don’t make those budget decisions on their own.

They work with committees charged with overseeing each school’s use of instructional dollars allocated by the state and federal governments to decide how they’ll use the money.

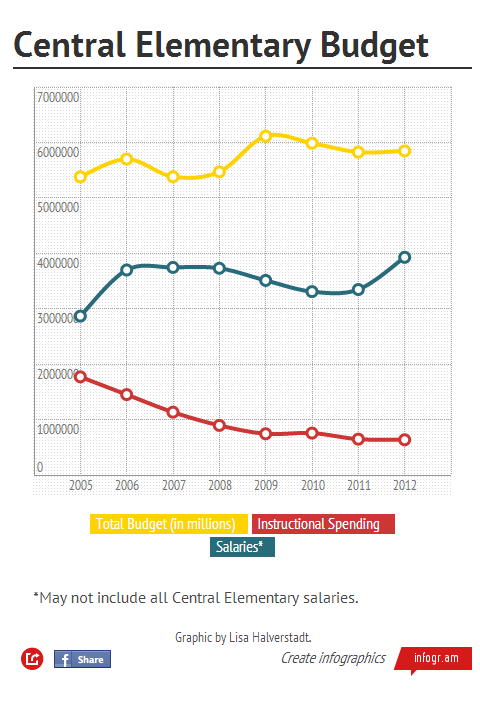

But as Central and other schools saw decreases in instructional dollars, which largely come from outside sources, overall budgets went up.

Here’s how the overall budget picture played out at Central.

You’ll notice the overall budget rose modestly over the past nine years, from roughly $5.4 million to about $6.1 million. Costs go up slightly each year but much of the increase can be attributed to automatic salary hikes known as step increases, which mandate raises for staffers after a certain number of years on the jobs.

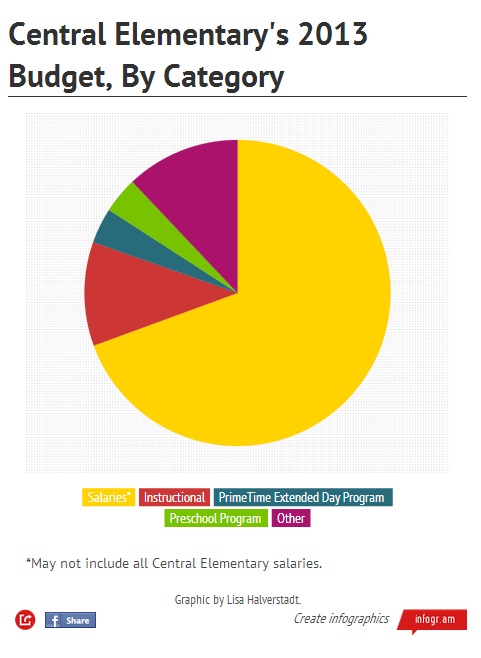

Those salaries dominate the school’s budget, as you can see below.