Cabdrivers are facing increasing competition from rideshare services like Uber. One reason consumers say they’re converting: they want to avoid that infamous archetype of the taxi industry – the smelly cabbie. The stereotype for predominantly immigrant drivers falls somewhere between playful and racist. But some in the industry say it’s flat-out wrong when it creeps into regulation. | Video Credit: Katie Schoolov, KPBS

By Megan Burks

Body odor isn’t exactly the easiest thing for Americans to talk about. So, as you do with awkward conversations, we’re going to ease into this one with a joke, courtesy of Jerry Seinfeld.

The smelly cabbie. Some in the taxi industry say the stereotype for predominantly immigrant drivers falls somewhere between playful and racist. But they say it’s flat-out wrong when it creeps into regulation – like the San Diego County Regional Airport Authority’s so-called “smell test” for cabbies.

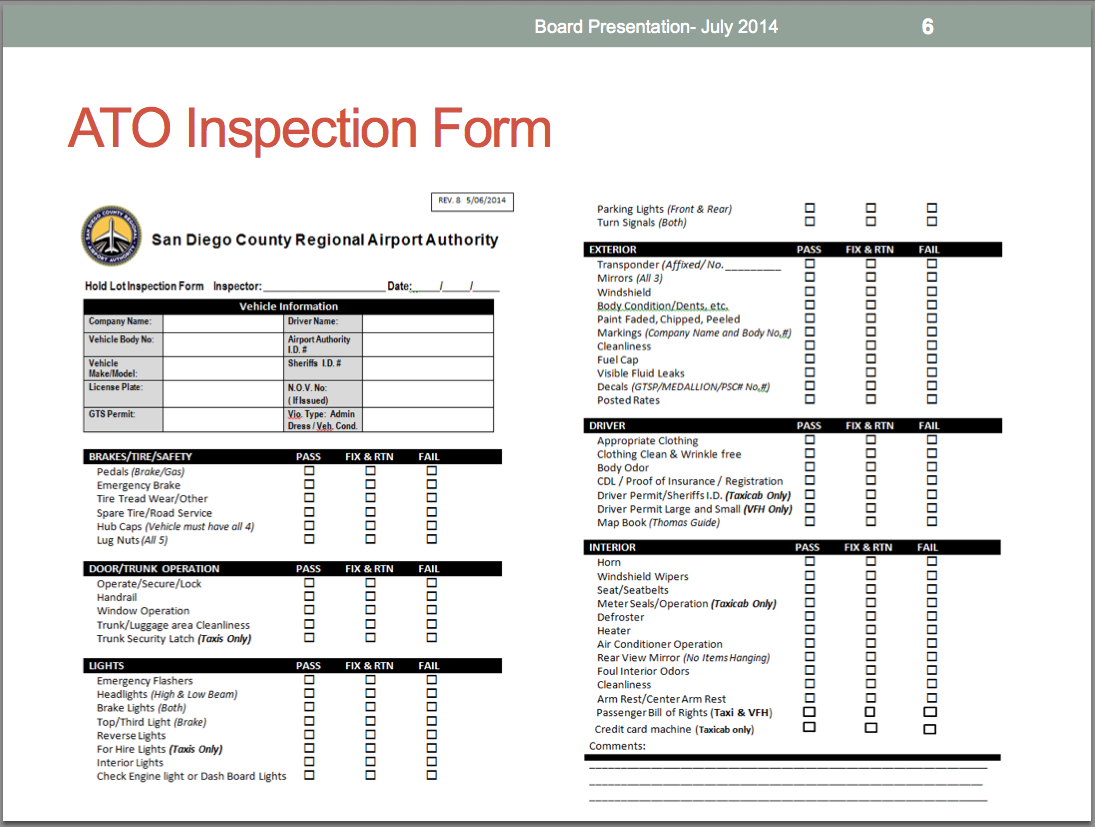

It shows up on a vehicle inspection form used by airport traffic officers. Alongside categories for brakes and headlights is one for driver body odor. If a driver gets a bad mark, inspectors can ask him or her to leave the airport’s taxi queue – and miss out on fares – until the unpleasant smell is taken care of.

The San Diego airport’s taxicab inspection form. | Source: San Diego County Regional Airport Authority |

Sarah Saez, an organizer with cabdriver association United Taxi Workers of San Diego, said the form crosses the line. And she’s not the only one. Seattle cabdrivers recently got detailed dress and smell regulations struck from their city’s taxicab policy.

“They’re adults and they get trained to do this. They’re businesswomen and men so I don’t think you need to do something as demeaning as a regulator coming and smelling you and checking off boxes,” Saez said. “It’s demeaning and it is borderline racist, I believe.”

Saez pointed out 70 percent of the city’s cabdrivers are East African immigrants. But airport spokeswoman Rebecca Bloomfield said the so-called “smell test” isn’t meant to be offensive. She said it’s about the customers.

“Our airport traffic officers who conduct these searches are very sensitive to cultural differences. Any type of violation of body odor is very extreme. It’s very rare,” said Bloomfield, recounting an incident where inspectors pulled a driver from the line because the smell was overwhelming once they opened the cab door.

It’s common for regulators throughout the United States to set detailed dress codes for drivers – right down to the height of their socks. Some also regulate cleanliness and smell. But Saez said such rules need to be put into context. She said the city’s majority immigrant cabdrivers deal with discrimination on a regular basis.

“It’s ongoing especially on a Friday or Saturday night, somebody has some liquid courage and they speak out against their driver,” Saez said.

Saez said drivers report passengers have called them “terrorists” and said some incidents have been enough for drivers to want security cameras installed in their vehicles. One driver, who declined to be named for fear of losing his job, said passengers have asked him to repeat street names over and over so they can laugh at his accent.

And Americans seem to have revived the smelly cabbie archetype as they talk about the rise of rideshare service Uber and why they made the switch to the slick alternative, including in this Voice of San Diego commentary:

Uber, Rideshare and Lyft are filling a void the taxi industry has left wide open – that of consumer choice.

Taxis – and drivers – come in various shapes, languages, sizes and smells. There are certainly excellent cab companies with excellent drivers, dispatch, radios and more, but those are the exceptions. The majority of people believe taxi drivers couldn’t care less about their passengers.

Fatima El-Tayeb teaches ethnic studies at UC San Diego. She says it’s not a stretch to think the anxieties about race and immigration fueling those backseat rants are also fueling the airport’s policy.

“You have this narrative of excess, right. (Immigrants are) too smelly, they’re too noisy, too many. And if a group is identified as excessive, what we have to do is stop them, to defend ourselves,” El-Tayeb said. “So it’s this kind of argument that allows measures that otherwise would be considered unacceptable, offensive, humiliating.”

El-Tayeb said smell has always been a part of the way people talk about and interact with disenfranchised groups – from the underclass of the Industrial Revolution to Jewish immigrants in Europe. She said it’s become so normalized people often miss the racist and classist undertones.

But Bloomfield said there’s nothing racial about the airport’s inspection. Inspectors only confront drivers about body odor, at most, a few times a year, she said.

“It goes back to the customer experience and we want to make sure that we provide a good one for the passengers flying into San Diego,” Bloomfield said.

And the airport is legally protected, said Susan Bisom-Rapp. She teaches labor law at Thomas Jefferson School of Law and said general hygiene rules are common in the workplace, though they often tiptoe around smell in case an employee’s body odor is a medical condition.

“Typically private-sector employers won’t say things like, ‘One must shower on a daily basis and use deodorant.’ But if there were to be a problem with the odor of a particular employee, a private-sector employer would deal with it very sensitively,” Bisom-Rapp said. “We’re in a different situation with the taxi drivers.”

That’s because they’re independent contractors. Labor and disability laws don’t apply to contingent workers, allowing the companies and regulators they work with to issue broad rules and regulations.

Bisom-Rapp said the smell test for taxi drivers may be legal, but said the assumption that immigrant cabdrivers need their body odor managed is troubling.

“I think before we pass rules like that,” Bisom-Rapp said, “we need to think deeply about what our core beliefs are about the people who are earning their living in this fashion.”