Sonia Weksler participates in an August 2012 WalkSanDiego study of El Cajon Boulevard and other business corridors in City Heights. | Photo Credit: Brian Myers

Sonia Weksler participates in an August 2012 WalkSanDiego study of El Cajon Boulevard and other business corridors in City Heights. | Photo Credit: Brian Myers

By Megan Burks

A group of City Heights residents assembled at the local library last month to learn about the latest study being conducted in their neighborhood.

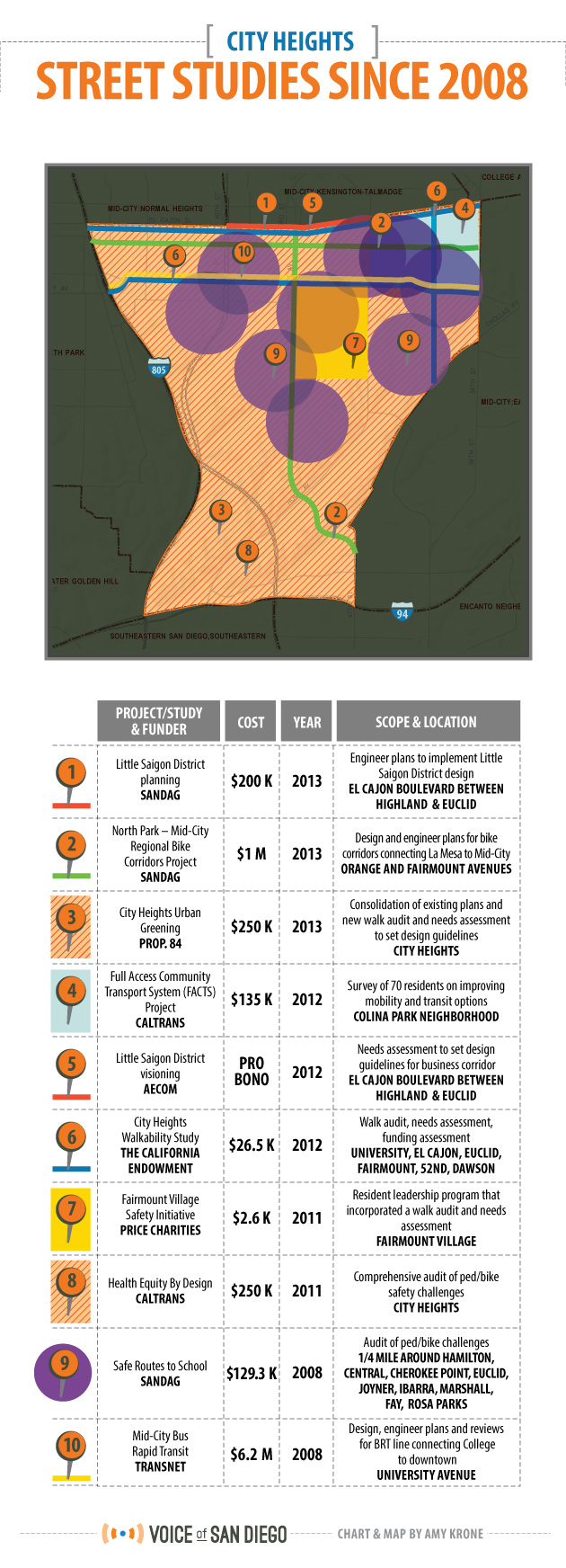

The City Heights Urban Greening project is a $250,000 city-led analysis that will result in a street design scheme and prioritize streets for improvement. It could be one of the most comprehensive studies of City Heights streets yet because of its scope — it’s looking at the entire community — but also because it’s incorporating the work of 13 other streets studies.

The residents at the meeting in the library have participated in just about all of those studies over the years. And it showed. As CHUG organizers explained the next steps (more outreach), the residents were racing ahead to the final phase (prioritization).

That’s because there haven’t been just 13 studies in the recent past. There have been at least 27 since 1998, totaling some $60 million.

Consensus is already there, and so is mounting frustration.

The vast majority of the studies did not include funds for construction or result in new infrastructure.

“If I had one wish, it would be to put a stay on any more studies,” said Samantha Ollinger, executive director of BikeSD and a City Heights resident.

Ollinger and others in the neighborhood have a case of “planning fatigue,” a phenomenon documented in places like Detroit and New Orleans, where residents are growing weary of an onslaught of post-recession and post-hurricane workshops and surveys. Sometimes they’re conducted by municipalities and have real funding attached. But often they’re organized by what some call “clipboard brigades,” volunteer groups trying to galvanize the community.

In City Heights, the planning brigades are borne out of infrastructure deficiencies common in dense, older communities. Development there occurred long before planners latched on to smart growth ideals. Years of disinvestment in street and sidewalk maintenance have further degraded conditions.

And with the arrival of private foundations Price Charities and The California Endowment in City Heights, community groups are applying for grants to work on these land-use issues at a feverish pace. (Disclosure: Speak City Heights is funded by The California Endowment but operates as an independent news collaborative.)

The Endowment has awarded about $2 million since 2009 for capacity building around infrastructure and transportation. During that time, 14 studies were conducted by community nonprofits.

Studies for Empowering, Not Building

Steve Eldred, the local program manager for the Endowment, said getting projects to the construction phase isn’t necessarily the primary goal of the grants his organization awards.

Community investment by nonprofits has shifted in recent years, from bringing tangible resources to communities to helping them go after the resources themselves. Grants are focused on leadership development rather than capital development.

“So no matter the extent to which the Endowment stays invested in the community, that capacity will still be there,” Eldred said.

Endowment grantees often bring residents together for walk audits and street surveys. They compile reports and create action plans, but their efforts are aimed at real-world learning, not immediate action. Eldred said residents do take their results to elected officials to advocate for solutions, but they’re learning as they go in an already backlogged system.

This slow, informal process, coupled with recent state laws and grants that are trying to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through smarter development, helps perpetuate the feeling that City Heights is over-studied and underfunded.

“There’s this idea that something is better than nothing, but sometimes it’s worse than nothing,” Ollinger said. “Because it gives the impression that something is being done.”

Funding for Planning, Not Implementing

Things are getting done in City Heights, albeit slowly. After about 30 years of advocacy work by the community, SANDAG is moving forward on construction of the Centerline, a bus rapid-transit line along Interstate 15. Another rapid bus route is slated for University Avenue. SANDAG is also moving forward on a bike route through the neighborhood.

But cobbling together infrastructure dollars for these projects took time.

Sherry Ryan, an urban planning professor at San Diego State, said there’s a wealth of planning grants available from outside sources like foundations. But construction grants are few and far between.

That disconnect, coupled with the end of redevelopment and strained city budgets, can make finding infrastructure dollars a pipe dream.

That’s especially true in City Heights, where neighborhood-specific revenue streams are already sluggish. Fees paid by developers that could go toward infrastructure projects in the community are set at less than 50 percent of the city’s average to help attract new development.

The neighborhood encounters another Catch-22 when it applies for SANDAG grants.

Its diverse demographics and existing deficiencies makes City Heights especially competitive for the agency’s planning grants. But those same infrastructure deficiencies handicap its ability to win construction grants.

The rubric for grading projects favors applicants in communities close to light rail. In two recent grant rounds, City Heights projects proposed for El Cajon Boulevard and University Avenue lost out to projects near the Coaster, in part, because there weren’t major transit facilities nearby, only bus routes.

SANDAG’s regional plan centers on a “city of villages” approach that would focus development near high-capacity transit hubs. City Heights advocates say their community is already a transit hub because of its network of bus lines serving a transit-dependent population.

Jay Powell, who retired from the City Heights Community Development Corporation in 2011 after leading it for two decades, said putting a halt to studies isn’t going to shake what locals are calling planning “exhaustion.” There needs to be a change in how dollars are awarded.

“It gets back to, how does the city as a whole prioritize?” Powell said.

Ollinger put it this way: “Coming up with a vision isn’t as important at this point as changing policy.”